CHONGQING, CHINA – OCTOBER 21: A worker walks through the exhibition hall for Chongqing New Model … [+]

In mid-July, China concluded an important economic policy meeting, where it dropped four times on technology as the center of its strategic plans and development.

Beijing is moving toward a four-pronged strategy that could challenge multinationals, boost Chinese competitiveness, and better position Chinese firms to position themselves in engineering across many emerging and frontier economies. :

- investing in innovation at the technological frontier, not least to reduce Chinese reliance on foreign supply and prevent it from being forced;

- using technology to transform traditional industries, especially manufacturing;

- exporting Chinese standards every time overseas customers buy Chinese products or technology, expanding China’s influence and creating compatibility or match-play challenges for international competitors; and

- further enabling technology and know-how to pass the price of access to China’s domestic market.

Another important decision of the conference, the Third Plenum of the Communist Party, which takes place every five years, is that China’s economic policy should use what Beijing calls “power new production” and “high productivity.” These words are a metaphor for encouraging innovation, but not as American and European policymakers fear, at the frontier of technology in emerging areas such as artificial intelligence and quantum computing. Limiting China’s access to these advanced technologies has become a priority for Washington and Brussels in recent years and they are using their regulatory and administrative tools to do so.

But Beijing may be pushing harder to use the technology culture industries, aiming to close China’s dominance of advanced manufacturing and compete with global rivals in “old” industries such as shipbuilding.

For Chinese policymakers, emphasizing technology as the key to development and competitiveness is not new in itself. The keynote of the Third Plenum, “new productive forces,” is a favorite of President Xi Jinping. But his more famous successor Deng Xiaoping, who introduced economic reforms in 1978, liked to refer to science and technology as “primary productive forces.”

Even under Chairman Mao Zedong, a revolutionary leader who promoted class struggle and a labor economy, Beijing held its nose and supported and encouraged advanced science and technology programs, making there have been frequent conflicts over national security and technological efforts to balance and try to keep pace with rivals, including Japan.

What has What has changed in the last 5-7 years is China’s national environment, which has been significantly damaged as US-China relations have deteriorated and Washington has continued to use foreign control and regulatory tools not only to reduce the flow of American technology to China but to influence and sometimes coerce partners. and partners to do so.

So part of the reason Xi is putting so much emphasis on technology is to better position China under American policy pressure.

For decades, US policymakers, firms, and investors viewed innovation and technology transfer as a business advantage—and the price of access to China’s large and promising market. But this is no longer the case. Now, the technology is “protected,” as policymakers and officials in Washington closely monitor China’s development of dual-use technologies, such as AI, quantum computing, and new artificial and artificial devices. combined, which have commercial advantages but also extensive military applications.

The Trump and Biden administrations, for two reasons, have strengthened America’s dominance of advanced technologies, such as nanometer-sized chips, to limit China’s ambitions in frontier industries.

They put in a lot of red tape, like the Trade Department’s List of Organizations, to make it difficult to transfer technology and skills to China. And they have cooperated with politically toxic Chinese technology firms – for example, by listing Chinese firms involved in any dual-use, whether state-owned or private, on the Department of Defense’s list of “military-related” companies, if they typically offer business, sales, or services.

Since almost all emerging technology is dual-use, this security trend can grow rapidly, causing US firms to avoid cooperation with Chinese partners for fear of being caught by the group. of Washington politics, policy or management.

Xi intends to combat this by investing heavily in domestic innovation. The US-China technology relationship will be defined in the next five years not by the joint efforts of the past 30 years to develop revolutionary technologies but rather by the balance between Washington’s influence to dominate and the Chinese are pushing for independence.

But indigenous innovation is the first pillar of China’s emerging strategy. The second and third could be decisive in enabling China to compete, and even dominate, in industries that are very important to many nations and market participants.

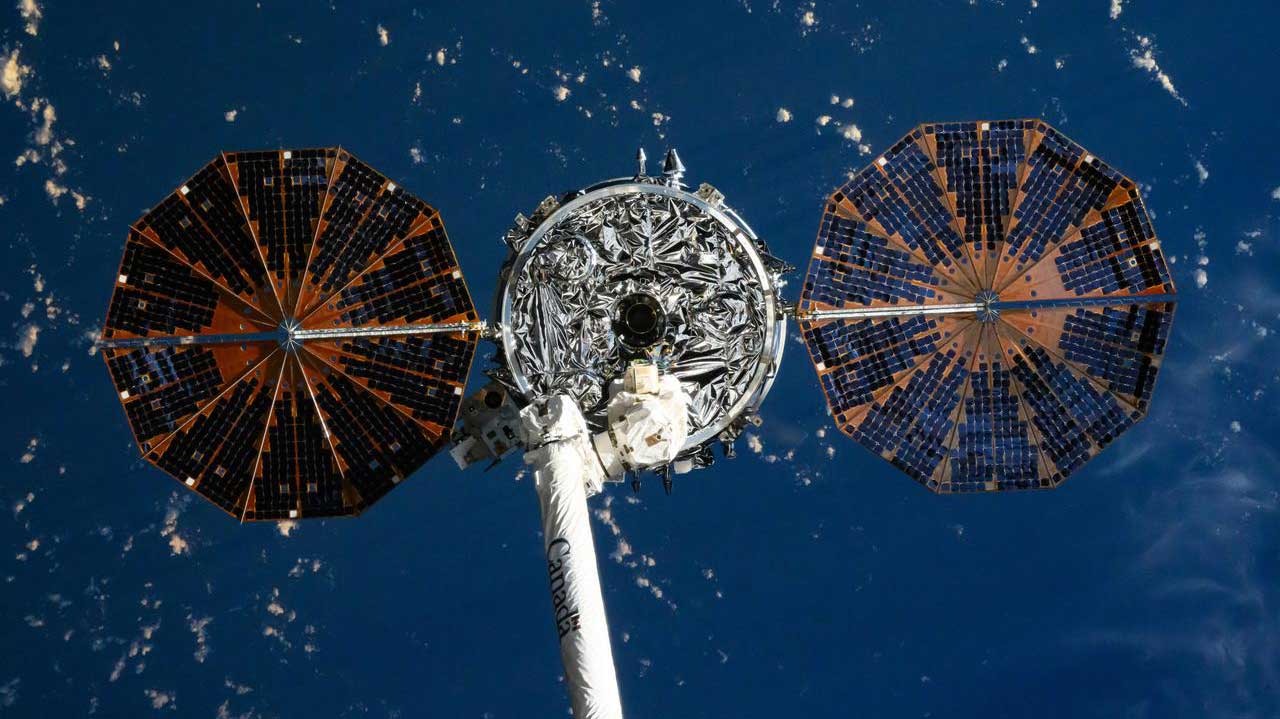

The second pillar—using technology in “old” industries to make them “new”—already works in traditional industries such as shipbuilding. AI and advanced computing can be used to design ship components and model how a ship can respond to emergencies and at sea. So Chinese designers and firms say publicly and privately that they want to speed up ship design by compressing their design times and using computer models to show customers every part of the ship before it is built. built. Similarly, Chinese firms are using AI for advanced manufacturing.

The third pillar – which makes China’s regional and global status – depends on China’s ability to raise the bar. The Washington think tank, CSIS, estimates that Chinese shipbuilders “now collectively account for 50 percent of all commercial tonnage produced worldwide each year.” And China has a large domestic population of 1.4 billion. By combining its strong domestic market power with its growing share of technology exports to the Middle East, Africa, Southeast Asia and beyond, China aims to make its industrial and engineering standards pacesetters. And if Chinese firms are first, global competitors who come later will have to, at least, adapt to China’s outstanding engineering or business standards in these markets.

By combining these three pillars, the elusive phrase “new productive forces” can generate tangible new benefits for Chinese firms around the world. And China is not abandoning the fourth and traditional pillar of its technology strategy. It continues to welcome foreign firms, albeit few of them and difficult conditions, as long as they continue to transfer technology and knowledge.

Some observers now argue that Beijing is no longer “accommodating” foreign firms or that the country has become “inefficient”. But the truth is more subtle: Beijing has made it clear during its post-COVID recovery that it wants foreign businesses as much as it does domestic players as long as they support and network closely with China. one economic development and industrial needs. If a company can help China move up the value chain or attract new technologies, processes and capabilities, it is still welcome.

That is why, even though foreign direct investment (FDI) in China has fallen sharply, falling to a 30-year low and decreasing by 28 percent from January to May, the Chinese government insists that “FDI spent” has not declined significantly. especially for advanced manufacturing. And internationalists are being asked to set up research and development centers in line with Beijing’s goal of encouraging the transfer of systems and skills.

For Beijing, the name of the game is to reduce policy vulnerability to foreign pressure, boost productivity, and leverage technology for market entry and positioning. And while many have dismissed China’s efforts at the border, this is only one pillar of its reform process.

It is very easy to underestimate “new productive forces” such as Communist manipulation when they exist. i strategy and method in what is thought to be madness. Taken together, and viewed over the long term, these four pillars include a concerted effort to challenge foreign players, plug vulnerabilities, and strengthen China’s competitive options.

Follow me first X and LinkedIn. And check out mine website and podcast.

#China #HighTech #Power #Economy #Upward